Greek art-has always been an area of symbolic surprises and physical beauty for scholars to study. Because of the ravages of history, only a minor assortment of ancient Greek art has survived - most frequently in the form of sculpture and architecture and minor arts, including coin design, pottery and gem engraving. Greece also has a rich history of contemporary art from the revolution onwards.

Hellenistic Era technically begins with the conquest of Alexander of Macedon in the years from 323 BC to 146 BC. Hellenistic sculpture repeats the innovations of the "second classicism": perfect sculpture-in-the-round, allowing the statue to be admired from all angles; study of draping and effects of transparency of clothing; suppleness of poses. My favourite art period in Greek history.

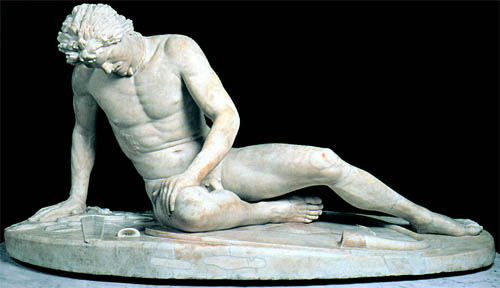

Dying Gaul

The Dying Gaul, a Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic work of the late third century BC Capitoline Museums, Rome.

The Dying Gaul is an ancient Roman marble copy of a lost Hellenistic sculpture that is thought to have been executed in bronze, which was commissioned sometime between 230 BC and 220 BC by Attalus I of Pergamon to celebrate his victory over the Celtic Galatians in Anatolia. The identity of the sculptor of the original is unknown, but it has been suggested that Epigonus, the court sculptor of the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon, may have been its sculptor.

The statue depicts a dying Celt with remarkable realism, particularly in the face, and may have been painted. He is represented as a Gallic warrior with a typically Gallic hairstyle and moustache. The figure is naked save for a neck torc. He lies on his fallen shield while sword and other objects lie beside him.

The statue serves both as a reminder of the Celts' defeat, thus demonstrating the might of the people who defeated them, and a memorial to their bravery as worthy adversaries. The statue may also provide evidence to corroborate ancient accounts of the Gallic fighting style – Diodorus Siculus reported that "Some [Gauls] use iron breast-plates in battle, while others fight naked, trusting only in the protection which nature gives.

The depiction of this particular Gaul as naked may also have been intended to lend him the dignity of heroic nudity or pathetic nudity. It was not infrequent for Greek warriors to be likewise depicted as heroic nudes, as exemplified by the pedimental sculptures of the Temple of Aphaea at Aegina. The message conveyed by the sculpture, as H. W. Janson comments, is that "they knew how to die, barbarians that they were."

The Winged Victory of Samothrace

The Winged Victory of Samothrace, also called the Nike of Samothrace, is a second century B.C. marble sculpture of the Greek goddess Nike (Victory).

Despite its significant damage and incompleteness, the Victory is held to be one of the great surviving masterpieces of sculpture from the Hellenistic period. The statue shows a mastery of form and movement which has impressed critics and artists since its discovery. It is particularly admired for its naturalism and for the fine rendering of the draped garments. The loss of the head and arms, while regrettable in a sense, is held by many to enhance the statue's depiction of the supernatural.

History- The product of an unknown sculptor, the Victory is believed to date to approximately 190 BC. When first discovered on the island of Samothrace and published in 1863 it was suggested that the Victory was erected by the Macedonian general Demetrius I Poliorcetes after his naval victory at Cyprus between 295 and 289 BC. Ceramic evidence discovered in recent excavations has revealed that the pedestal was set up about 200 BC, though some scholars still date it as early as 250 BC or as late as 180. Certainly, the parallels with figures and drapery from the Pergamon Altar (dated about 170 BC) seem strong. However, the evidence for a Rhodian commission of the statue has been questioned, and the closest artistic parallel to the Nike of Samothrace are figures depicted on Macedonian coins. The most likely battle commemorated by this monument is, perhaps, the battle of Cos in 255 BC, in which Antigonus II Gonatas of Macedonia won over the fleet of Ptolemy II of Egypt.

Laocoon and groups

The statue of Laocoön and His Sons, also called the Laocoön Group, is a monumental sculpture in marble, attributed by the Roman author Pliny the Elder to three sculptors from the island of Rhodes: Agesander, Athenodoros and Polyclitus. It shows the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus being strangled by sea serpents.

The story of Laocoön had been the subject of a now lost play by Sophocles, and was mentioned by other Greek writers. Laocoön was killed after attempting to expose the ruse of the Trojan Horse by striking it with a spear. The snakes were sent by Athena, and were interpreted by the Trojans as proof that the horse was a sacred object. The most famous account of these events is in Virgil's Aeneid (See the Aeneid quotation at the entry Laocoön), but this very probably dates from after the sculpture was made.

Various dates have been suggested for the statue, ranging from about 160 to about 20 BCE. Inscriptions found at Lindos in Rhodes date Agesander and Athenedoros to a period after 42 BC, making the years 42 to 20 the most likely date for the Laocoön statue's creation.

No comments:

Post a Comment